Brooklyn

Long Island

Brooklyn, New York | Aug 27, 1776

George Washington’s efforts to fortify New York City from a British attack led to the Revolutionary War’s biggest battle. The crushing defeat for the Americans allowed Britain to hold the valuable port until the end of the war.

How it ended

British victory. Shortly after fighting began, the British cornered Washington and 9,000 of his men in Brooklyn Heights. He was surrounded on all sides with the East River to his back and no feasible means of winning the battle. Instead of surrendering, Washington evacuated the army and retreated to Manhattan, a decision that saved the Continental Army and the patriot cause.

In context

New York played a pivotal role throughout the American Revolution, particularly early on. Its central position in the American Colonies and its port made it vital to commerce and a key strategic location. After compelling the British evacuation of Boston in the early months of 1776, General George Washington accurately guessed that the Redcoats’ next target would be New York City. Washington transferred his Continental Army to the city in April and May, hoping to turn back or at least severely cripple the next wave of British invaders.

The Continentals fortified the city in fits and starts. Discipline was sorely lacking among the Americans, many of whom had never been so far from home and had never served in a professional military. They were awed by the arrival of the British fleet in late June. One man remarked that it looked like "all London afloat." The British infantry disembarked on Staten Island.

The British warships had the potential to dominate the river waterways that cut through New York City, rendering the American defense untenable. Nevertheless, Washington sought to fight a battle and inflict some damage before abandoning his position. His defensive arrangement, however, was fatally flawed. He split his forces between Brooklyn and Manhattan, preventing easy reinforcement or escape across the Hudson and East Rivers. Furthermore, his line atop Guan Heights did not stretch to cover the Jamaica Pass, a hole that was exploited by British regulars.

Although a timely retreat saved the Continental Army from destruction at Brooklyn, Washington’s failure there left New York firmly in British hands until the end of the war.

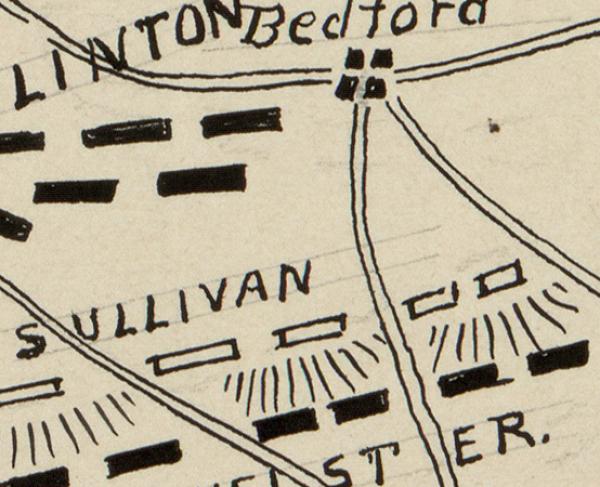

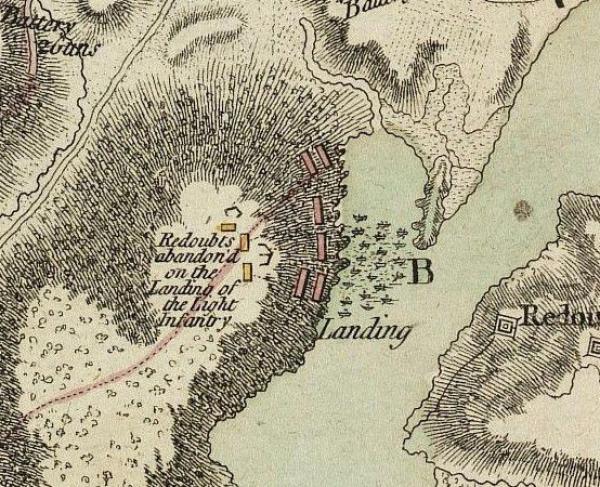

On August 22, British transports move 10,000 infantrymen to Long Island. Wrongly thinking that this is a diversion for a main attack on Manhattan, Washington does not recombine his forces to meet the new threat. British general William Howe, hearing from Loyalists in the area about the undefended Jamaica Pass, sends an advance force there. At the same time, he orders British and Hessian troops to distract the Continental soldiers from the front. The Redcoats march into position on August 26. On August 27, the British launch an attack on the Americans.

August 27. The Americans are in two lines: Guan Heights to the south and Brooklyn Heights farther north. The fighting for Guan Heights rages throughout the morning. British troops filter through Jamaica Pass and break through several other American positions, eventually gaining control of the ridge. The battle's bloodiest fighting occurs near Battle Pass, where Hessian mercenaries fight the patriots hand-to-hand.

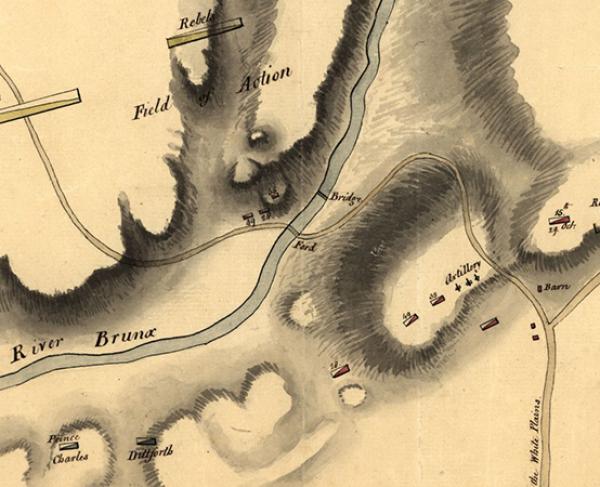

As the Americans pull back towards Brooklyn Heights, one contingent is nearly surrounded by the onrushing British. About 400 Maryland soldiers, now known as the Maryland 400, countercharge to buy time for their comrades to escape. More than 250 Marylanders are killed as they fight desperately against the British legions, but the rest of the army manages to retreat safely.

By nightfall, the Americans are hemmed in on Brooklyn Heights with the East River behind them. General Howe overrules subordinates who argue for a renewed assault, instead entrenching and preparing to lay siege to Washington's army.

Washington, however, does not consent to a siege and eventual surrender. In the dark of night, he coordinates a retreat across the river without losing a single life. When the British probe the American lines, they find them empty.

2,000

388

Despite his tactical defeat, Washington scores strategic points by keeping his army intact, but many Continental soldiers are imprisoned on British prison ships in New York Harbor, where they suffer under horrible conditions. New York City is lost, and the British hold it for the remainder of the war. When the United States finally regains control of the city in 1783, the fledgling government wastes no time in fortifying New York Harbor.

Trapped by the British, a group of Maryland troops led a series of dramatic charges that held the Redcoats at bay long enough for the Continental troops to escape safely from the battle. This brave action cost the regiment hundreds of lives, but saved most of the Continental Army.

The First Maryland Regiment was the first group of troops Maryland raised at the beginning of the Revolutionary War. In July 1776, a few days after independence was declared, the regiment was ordered to New York so it could join the forces of General George Washington. The regiment arrived there in early August. A few weeks later, it faced the British Army at the Battle of Brooklyn.

During the rout at Brooklyn, the Maryland troops fought their way back towards the American fortifications but were forced to stop at Gowanus Creek. Half the regiment, including the First Company, was able to cross the creek and escape the battle. However, the rest were unable to do so before they were attacked by the enemy. Facing a much larger, better-trained force, these troops, now known as the Maryland 400, mounted a counterattack that saved many of their fellow soldiers. As the Marylanders began to fall, Washington cried out, ‘Good God! What brave fellows I must this day lose!’

In all, the First Maryland lost 256 men, killed or taken prisoner, and some companies lost nearly 80 percent of their men. Major Mordecai Gist, who led the Marylanders, survived to fight in many other crucial battles of the Revolutionary War and was present at the surrender of the British at Yorktown in 1781.

Many taken prisoner after the Battle of Brooklyn, as well as those captured by the British in other battles, were held aboard decaying warships that were anchored or had run aground in New York Harbor. With their dominant naval power, the British had seized New York’s strategic port and used it as a depot for troops and supplies as well as a floating jail. In the course of the Revolutionary War, more than 8,000 Americans died in combat but far more—over 11,000—died as prisoners, either in hulking wooden vessels (“hulks”), abandoned churches, "sugar houses" (or refineries), or in squalid buildings scattered around the colonies.

The hulks in New York’s waterways, were considered floating coffins. Prisoners were forced to eat moldy bread, rancid meat, and "soup" made with toxic water from the East River. Disease was rampant, and corpses were routinely tossed overboard. Thousands of remains eventually washed up along the Brooklyn shore. In a July 1778 edition of the Connecticut Gazette, Robert Sheffield, a survivor of a hulk in Wallabout Bay (now the Brooklyn Navy Yard) recounted his experience:

Thomas Andros, a prisoner held with about 1,000 other men on the Jersey, nicknamed “Hell” by the captives, wrote of his experiences after the war:

Even after the British surrender at Yorktown in late 1781, prisoners were kept aboard the Jersey and other ships until the war formally ended in 1783. When the new U.S. Navy occupied Wallabout Bay and began expanding the Brooklyn Navy Yard on the mud flats near the shore, they found the bones of thousands who had perished aboard the British prison ships. These were collected and buried on the grounds of a nearby estate. They were moved to a more permanent site in 1808 and reinterred at Fort Greene Park in Brooklyn in 1873. In 1908, President William Taft dedicated the grand Prison Ship Martyrs Monument there. Beneath the 150-foot-high obelisk lies a crypt with 20 coffins containing many of those bone remains.

Brooklyn : Featured Resources

All battles of the New York and New Jersey Campaign

Related Battles

10,000

20,000

2,000

388