The Fight at Brown's Ferry

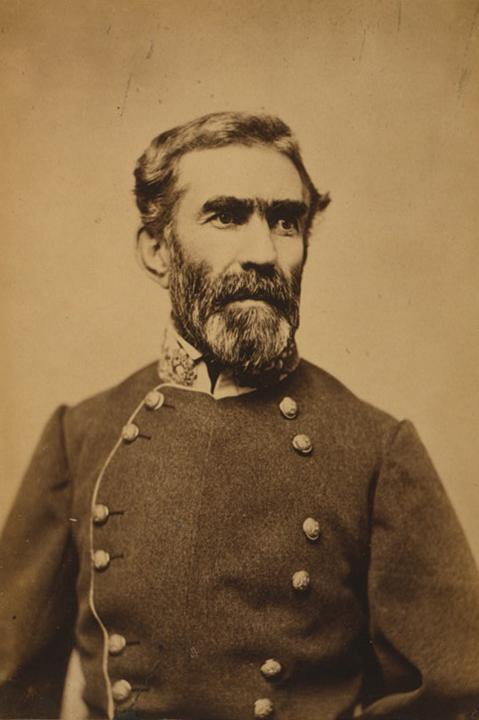

After a near debacle at the Battle of Chickamauga, the Union armies were able to retreat to the city of Chattanooga under the heroic efforts of Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas. The Union retreat allowed Confederate General Braxton Bragg to lay siege to the city to starve the Union out. Times were getting desperate and the Union commander at the time, Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, was folding under the pressure. Something had to be done to provide relief to the Union forces in Chattanooga.

It was raining when Ulysses S. Grant arrived in Chattanooga on the night of October 23, 1863. Foremost on his mind was the relief of the city, where thousands of Federal troops had been essentially cut off from the outside world by Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. “[R]ations and forage were about exhausted,” remembered Capt. Horace Porter, “and almost the last tree-stump had been used for fuel.” Shortages of overcoats and shoes contributed to the misery of the troops while pangs of hunger affected both man and beast alike. Worse, the army had only enough ammunition for one day’s battle, so despite Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas’ determination to “hold the town till we starve,” it was obvious that something needed to be done and soon.

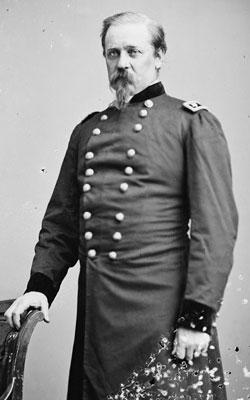

Thomas’s chief engineer, Maj. Gen. William F. “Baldy” Smith, pitched a daring idea to a wet and weary Grant on his first night in Chattanooga. Smith had been secretly hatching a plan to bridge the Tennessee River and open a route of supply called the “cracker line”—a reference to the notoriously hard crackers called hardtack. The Vermont native had even begun accumulating a number of flat-bottomed boats to transport men down the river, just under the Confederate guns on Lookout Mountain. Once they passed the guns, they would land on the left bank of the river and establish a bridgehead there while additional troops paddled across the river from the right bank. With a crossing point firmly established, Thomas’ troops would link up with men from the Eleventh and Twelfth corps under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, who were at that moment marching toward Chattanooga from the southwest, and reopen the city’s supply line. It was an audacious plan, but the situation at Chattanooga called for exactly that, and Grant was a more than willing accomplice.

The following morning, Smith, Thomas, and Grant rode to Smith’s proposed crossing site, Brown’s Ferry. The proposed route of supply, a road leading across Raccoon Mountain, sat on the opposite bank in a gorge between two hills. These hills could easily be fortified to protect the bridgehead until Hooker’s men arrived. True, the riverbound troops might be seen by enemy pickets, but in the weeks since the siege began, the relations between belligerents had become so lax that Grant, Thomas, and Smith stood in plain view of the Rebels without drawing their fire. With a little luck and a lot of care, Smith believed that a body of men silently floating down the river in the dead of night could get the drop on their opponents before the alarm could be sounded. Grant was willing to take the gamble and gave Smith’s plan his hearty endorsement.

On October 25, Brig. Gen. William Hazen learned that he was to command the Federal operation. After making a reconnaissance, Hazen divided his command—a brigade comprised of nine regiments from Indiana, Kentucky, and Ohio—into two forces.

He organized the first, into 50 squads of 24 men and one officer, which would ride the boats down the river and force a lodgment on the hills above Brown’s Ferry. Each squad carried two axes so they could immediately fortify their bridgehead. Lt. Col. James Foy of the 23rd Kentucky commanded a special detachment of 75 men, which would make the initial landing then penetrate inland. The 1st Ohio’s Lt. Col. Bassett Langdon commanded the balance of Hazen’s brigade, which would ferry across the river after the bridgehead was established. For additional insurance, Brig. Gen. John Turchin’s brigade would reinforce Langdon’s command. The operation was scheduled for the pre-dawn hours of October 27.

Hazen’s command went into motion shortly after midnight on October 27 and encountered problems almost immediately. First of all, the boat designated for Colonel Foy’s 75 men could in fact only hold 50. Foy ordered his captains to strip their teams to 16 men each, for a total of 52 in men in the first wave; the remainder would wait with Colonel Langdon. As if this weren’t bad enough, Foy also discovered that his boat was laden with heavy pieces of scrap iron that had to be removed. He and his men then had to portage the boat 300 yards overland to the actual point of departure.

Meanwhile, Colonel Langdon’s men marched to Brown’s Ferry only to find the staging area choked with artillery and the sleeping men of Turchin’s brigade, who had arrived earlier. These factors, no doubt exacerbated by the usual frustrations of moving large numbers of men in the dark, delayed the departure of Hazen’s force until about 3:30am.

In the pre-dawn darkness, the ominous peak of Lookout Mountain loomed overhead as Hazen’s men floated down the river. It was tense. Confederate pickets lined the opposite shore, ready to fire on the defenseless Yankees if the expedition was discovered. Suddenly, a splash and a cry rent the night. A low-hanging branch had struck a man on Foy’s boat, knocking the poor soldier into the water. He was scooped out of the river by the next boat, apparently unharmed, as many surely wondered whether the Rebels would respond to the strange sound. Thankfully for Foy, the enemy seemed not to notice and the boats toward the two signal fires that marked the position of the landing site.

Foy angled his boat toward the far bank, with the help of General Hazen, who shouted course corrections from further back in the flotilla. When the Federals were about 100 yards from the shore, the Confederates let loose a volley. Instinctively, a handful of Foy’s men returned the fire before their officers could silence them. Too few in number to resist the landing party, the Rebels apparently fled the scene as Foy’s men occupied the gorge without further incident. They proceeded inland to secure the road to their front. Meanwhile, the remaining parties ferried ashore, scaled the bluffs overlooking the Tennessee River, and began felling trees and erecting fortifications. The first major objective of General Smith’s operation—crossing the river—had been achieved.

Foy’s men did not go unnoticed. Just before sunrise, a panicked Confederate awakened Col. William C. Oates of the 15th Alabama, who commanded the troops in this sector. Oates immediately formed his regiment and marched toward the sound of the Yankee axes. As he was about to pounce on Foy’s unsupported troops, the Kentuckians, who had heard Oates’s approach, bolted for the safety of their breastworks. “[A]dopting their usual plan of cheering and firing at the same time,” Oates pursued the heavily outnumbered Kentuckians, who poured lead into the Alabamians. Foy sent for help but couldn’t wait long enough for it arrive. Again his 52 men fell back, closer and closer to the inchoate bridgehead at Brown’s Ferry.

Colonel Langdon’s men were still in the act of disembarking when a breathless man from Foy’s detachment reached him. Langdon sent the man to find Hazen, promising to send the balance of the 23rd Kentucky to Foy’s aid. “Hardly had this messenger gone 20 paces on his return when a rattling fire opened down the gorge in front.” To meet this obvious threat, the Ohioan ordered the 6th Indiana, then in the act of struggling up the bank, to reinforce Foy. Two lieutenants of the 6th Indiana collared as many men as they could and rushed to the front, just as the shadows of Foy’s party could be seen edging further into the gorge and closer to the shore.

Though Oates temporarily succeeded in driving back Foy’s advanced party, by the time the Confederates arrived within sight of the river, the Yankee force had reached a critical mass. Foy was reunited with the remainder of his regiment and fragments of other regiments now occupied the hills overlooking the gorge. Oates was caught in a deadly fire before the 41st Ohio—the last regiment to arrive—impetuously charged up the road and drove the Confederates away from the bridgehead for good. According to Colonel Langdon, “we were masters of the gap.”

The fighting at Brown’s Ferry did not end the siege of Chattanooga, but the first major step had been taken. The following day, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet launched a feeble effort to sever the Cracker Line by attacking the Twelfth Corps at Wauhatchie. By then, however, it was too late. Grant’s men had bridged the Tennessee River and the tide at Chattanooga was about to turn.

Help the Trust save 161 acres across consequential Western Theater battles — Fort Heiman and Fort Henry, Brown’s Ferry/Chattanooga, Spring Hill, and...

Related Battles

5,824

8,000