"Independence Day Celebration in Centre Square, Philadelphia" by John Lewis Krimmel

A wave of national pride swept through the United States at the conclusion of the War of 1812 and the approval of the Treaty of Ghent in Congress in February 1815. The war had served to unite Americans, and they believed they had won a successful victory over the British, preserving their independence and national sovereignty. The lack of resolution of the war causes, the burning of the nation’s capital and the exposed weakness of the United States military system did not readily factor into the victory narrative.

The ending of the War of 1812 marked a brief period in United States History referred to as the “Era of Good Feelings”—a few years of prosperity, lessening of political division, and interest in projects for the national good. This proverbial calm before the storm preceded the Jacksonian Era which was characterized by the rise of new and powerful political parties, sectional interests, and increasing tension over slavery. These two eras set the stage for the more tumultuous decades of the 1840s and 1850s which pushed the country closer to the brink of civil war.

From approximately 1815 to 1825, the United States turned inward, enjoying the feelings of victory, peace and prosperity in the first few years of the era. A Boston newspaper editor dubbed the period the “Era of Good Feelings” in July 1817. Other writers followed the trend with mixed seriousness and part sarcasm. “…The ecstasy of the bliss of the political Millennium and the era of good feelings,” chirped one newspaper later that year, proclaiming, “To the peaceable and the pious it must be truly delightful to trace the effusions, ‘the good feelings of a whole people.’”

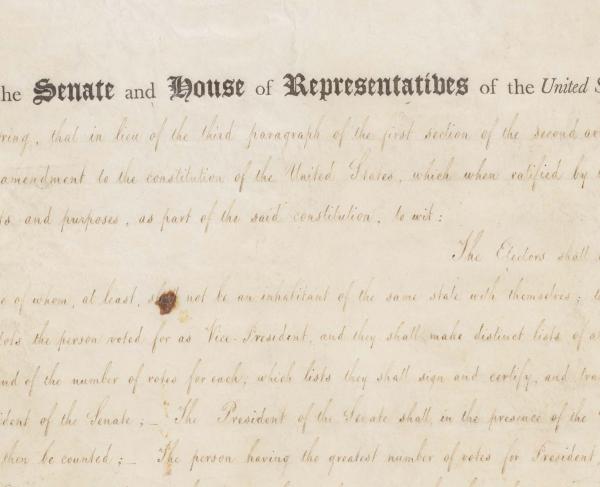

Economic prosperity grew between 1815 and 1819, encouraged by a new protective tariff, the founding of the Second Bank of the United States, and new transportation networks linking regions of the nation. The Tariff of 1816 protected American manufactory from foreign competition and prevented raising certain taxes to reduce the federal deficit; the Tariff received rare support from the Southern states, partly because it did not significantly impact their imports and also because it was a temporary three-year tariff. The Second Bank of the United States built on Alexander Hamilton’s precedents and was chartered in 1816. It encouraged the expansion of credit while unable to regulate private banks, hold a large reserve, or set financial policy. Credit and land speculation in the west primed the American economy for a collapse. Rapid expansion into the Midwest and beyond the Mississippi River into the Louisiana Purchase—encouraged by the economy in the early years of the Era of Good Feelings—overlapped with intentional improvements for transportation between states and regions. The National Road, started in 1806, reached Wheeling, Virginia (West Virginia) in 1818 and plans were approved to extend this thoroughfare to St. Louis on the Mississippi River; the National Road set an example for other major construction projects across other regions. Canals, like the Erie Canal and Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, were started in this era and became valuable pathways for transporting agricultural crops.

Contributing to the “good feelings” was the perception of unified politics. The Federalist Party had dissolved, leaving the Democratic-Republican Party in control of state and national politics. Kentuckian politician Henry Clay championed “the American System” which formalized and politically encouraged the prosperous innovations. It focused on protective tariffs, high public land prices to create federal revenue, strengthening the Bank of the United States, and using tax and tariff revenue to build internal improvements. The strength of the American System’s concept offered something preferential to each region. Though ideal on paper, the system did not perform as equally as Clay and his supporters envisioned.

Protecting national interests fueled some of the diplomatic decisions and efforts during President James Monroe’s administration and the Era of Good Feelings. After years of wrangling and treaties, the land of Florida was officially added to the United States holdings through the Adams-Onis Treaty in 1821. The Monroe Doctrine, outlined in a message to Congress in December 1823, pledged to oppose European colonization in North and South America and would stay out of Old-World affairs in return. Admirers of the United States made significant visits during the peaceful years, including the Marquis de Lafayette, the last surviving major general of the Revolutionary War, who toured the country during 1824-1825.

Despite the ideals and innovations, fractures threatened the Good Feelings and foreshadowed the next era of American history. In 1819, an economic depression slumped the prosperity as credit collapsed and local banks could not back their printed money. The Missouri Compromise in 1820 allowed Maine to become a free state while Missouri joined as a slave state—keeping the balance of slave and free states in the U.S. Senate—while outlawing slavery above the 36º 30' latitude in the rest of the Louisiana Purchase territory. Though a compromise was reached, the questions of expanding or limiting slavery, free states and slave states, or abolition enforced at the national level firmly entered American political discussion.

James Monroe’s second presidential term came to an end, and the Election of 1824 brought the two-party political system back with the rise of the Whig Party debating the Democratic-Republican Party. John Quincy Adams won the presidential election, becoming the sixth president and the first son of a former president to take office. He supported a continual of the American System, but sectionalism and political differences grew during his one term presidency.

Andrew Jackson—hero of the War of 1812 and a Tennessean—won the Election of 1828 on the Democratic-Republican ticket. His political victory was seen as a triumph for the western section of the country and for the “common man.” Political and social changes marked the Jacksonian Era (1829-1854) and are sometimes referred to as Jacksonian Democracy which focuses on the concept that people’s will is sovereign in government and the majority voters rule. Some historians have identified changes and hallmarks of Jacksonian Democracy, including Manifest Destiny, expanding voting rights, strict constitutionalism, laissez faire, opposition to national banks, and patronage.

Manifest Destiny called for the expansion of the United States from the Atlantic to the Pacific, often inserting religious justification into the political and social movement. While many Americans believed in Manifest Destiny, they divided on the specifics—debating if the new territories and states should be slave or free states. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the American interest in the Battle of the Alamo (1836) and Republic of Texas are some of the early, controversial outcomes of Manifest Destiny.

To make voices heard on issues like Manifest Destiny, voting rights expanded for white male voters. States ended property owning requirements for voting and poll taxes. African Americans, Native Americans, some immigrants, and women did not have suffrage rights yet, but the expansion of voting rights beyond property ownership was still significant.

While Jacksonian Democracy put emphasis on popular voting and the spirit of the common man, it also clung to a strict and literal interpretation of the United States Constitution. Following in the political footsteps of Thomas Jefferson, this view limited the expansion of the federal government and kept powers to the states. Andrew Jackson himself spoke for national unity; while he supported elements of states rights, he spoke against secession during the Nullification Crisis. The strict constitutionalism also influenced economic policies. Over time, the concept of strict constitutionalism came under ridicule as the Jackson Administration attempted to expand the power of the presidency.

Economically, Laissez-Faire (French for “hands-off”) characterized Jacksonian Democracy. While the Whig Party advocated for railroads and federally backed banking, the Democrats preferred a “hands-off” policy and particularly opposed the national bank. The idea was to allow local and state economies to evolve without restriction or support from the federal government.

The Second National Bank became a topic of deep debate following the War of 1812. Jacksonians and Democrats opposed the concept of a central bank, believing that it created a government-formed monopoly. Jackson thought that banks were designed to cheat people and preferred hand currency instead of bank credit. The Whig Party followed in the principles of Alexander Hamilton, hoping for economic development and growth through a central bank. Ultimately, Jackson ended the Second National Bank during his presidency.

Patronage or the “Spoils System” also characterized the Jacksonian Era. This concept placed political supporters in political offices, whether or not they were qualified for the position. Although this seems in opposition to some of the other characterizing thoughts of Jacksonian Democracy, the idea theorized that it would be good to empower the “common man” to take part in government, those appointees would help to hold prominent political leaders accountable and prevent long tenure of office. The idea backfired, though, as many unqualified individuals took political offices. President Jackson’s political enemies accused him of favoritism and poked fun at this system.

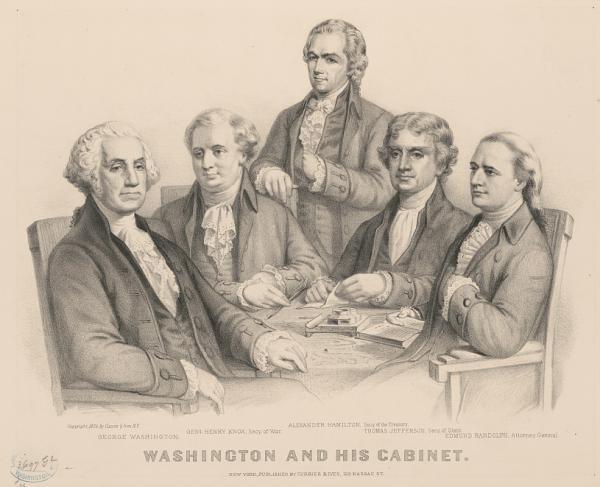

The Era of Good Feelings and the Jacksonian Age are political bridges between the United States victory in the War of 1812 (1812-1815) and the American Civil War (1861-1865). The political changes fostered national and sectional pride, territorial expansion, increasing popular sovereignty among voters, and the growing concept of the “common man” transformed American politics from the era of the Founders.